|

|

Using any kind of media to change attitudes carries a very real danger of policy-backfire that will actually make things worse. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

You can read my latest blog post on this topic (November 2012) here: Don’t be a Clownmonger: Beware the unintended consequences of unevidenced compellingly plausible initiatives

Do Media Initiatives Change Attitudes in the Desired Direction?

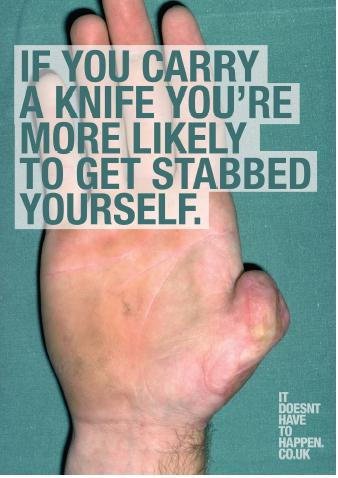

How do we know whether or not attitude change poster and other media campaigns devised by committees, advertising executives and young people with no knowledge of the psychology of attitude change have had the desired effect? Could they actually make things worse and backfire? How do we know, for example, that anti-knife crime posters such as the one on the left do not make people more fearful of knife attacks and lead them to arm themselves for self defence?

|

|

|

This is an important and much neglected area. Research that I conducted with colleagues for the British Government reveals that an overview of the literature on what works in the use of media for attitude change is complex and often counterintuitive. Campaigns that are not properly designed, targeted and piloted run a great risk of making worse the problem they seek to reduce. You can read the full report here. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Clowns Fallacy

A study published in The Nursing Standard Magazine reveals that what children like can be counterintuitive to adult beliefs about children's' likes and dislikes.

Research involving 250 children in hospital revealed the dangers of intuitive and well intentioned schemes and exposed an example of the harmful folly of adults who decided to decorate children's' wards with clown pictures to make them feel safe and happy. Because it had exactly the opposite effect.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Crime Prevention Poster Campaigns

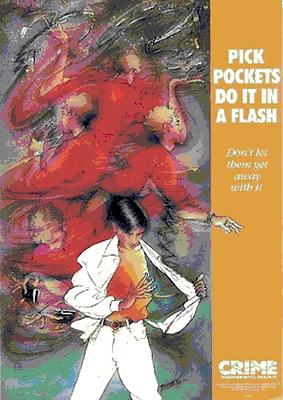

According to Paul Ekblom, pickpockets admitted to lurking by signs designed to warn potential victims in order to see where people reassuringly patted their wallets. This then made picking their wallets much easier.

This story is mentioned at page 120 of Clarke, Ronald. V. (1995) Situational Crime Prevention. In Tonry, M and Farrington, D. P.(eds) Building a Safer Society: Strategic Approaches to Crime prevention. Crime and Justice A Review of Research Edited by Michael Tonry. Volume 19. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. The actual study that Clarke cites is Ekblom P (1991) Talking to offenders: Practical Lessons for Local Crime prevention. In Urban Crime: Statistical Approaches and Analysis. Edited by Oriol Nel-o. Barcelona: Insitut d’Estudis Metropolitans de Barcelona.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

‘Race’ and ethnic prejudice reduction and other attitude change

Uninformed intuitive good intentions may have the opposite to intended effect in sensitive areas of social policy where 'race' and ethnic bias is involved and where prejudice and attitude change is the goal. Uninformed initiatives can actually increase the prejudice and victimisation that they are seeking to reduce.

|

|

|

The British Government's Department of Communities and Local Government was keen to implement an initiative that involved recruiting 20 black (male) role models so that (as I was informed in a meeting with them in London) young black "youth" can aspire to other occupations beyond rapping and sports.

The initiative was designed by an advertising executive who was paid by the Department of Communities and Local Government. When I met with him and the civil servants in London who commissioned the project to discuss it just prior to its launch I was accompanied by two professors of psychology - both experts in the best use of media in attitude change. All three of us advised that the project was a risky strategy. The advertising expert and civil servants were genuinely surprised to hear that years of research suggests that all initiatives such as theirs should be tested in a pilot study first to ensure that they have a fair chance of changing the attitudes of the target audience in the right direction and also to ensure that they do not increase prejudice among other groups.Testing it in this way first would have at the least enabled the project team to fine tune the initiative in order to help make it most effective. Since so much had been invested in the project already, and a press launch had been booked, they felt that they had no choice but to launch the project anyway. You can see it here. Intuitively it seems fine to me. But is it? Who can claim to know? What about all the ethnic groups that have been left out? Does it, for example, make sense to include those who might define themselves as mixed black-white people in with those of black African heritage given that research in this area finds that such media initiatives work best if they target only one very specific group at a time if they want to influence people in that group?

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The London Olympic Logo

The London Olympic Logo was designed in July 2006 by Wolf Olins, a marketing company, and was approved by the London Organising Committee for the Olympic Games. Chair of the committee, Lord Sebastian Coe said that the logo is not meant to appeal to those people who do not like it. Rather, Coe believes that it will help our ‘youth’ to embrace the Olympic ideal by way of its graffiti style.

I have been unable to find a shred of evidence to support this expensive notion. But if you Google 'London Olympics Logo' you will soon see that it is very widely hated and ridiculed.

The £400,000 that was paid to the Wolf Olins company to design the thing came from private sources. But that is hardly a rational justification for Britain, as the host nation, to accept it as worthy of representing them.

You can read the unsupported and therefore irrational reasoning of the London Organising Committee for the Olympic Games here:

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

Media For Attitude Change |

|