Please note: Theft of a person’s original ideas or written work is theft of their time. Since time is perhaps the most valuable commodity we have, please respect the usual rules of copyright and academic citation. The original content on this page and on the entire Dysology website is protected by USA and European laws of copyright and also by standard universal and local academic rules and regulations regarding plagiarism. All rights reserved. © Dr Michael (Mike) Sutton.

One way to cite this page:

Crime Opportunity Theory is wrong because the RAT classic crime triangle that is used in the theory to represent an opportunity cannot be an opportunity since it does not allow for the fact that in reality opportunities are not objective entities and they are not certainties. Moreover, to be an opportunity the conjunction of favourable factors must be perceived by a person who can then decide whether or not to seek to capitalise on the situation.

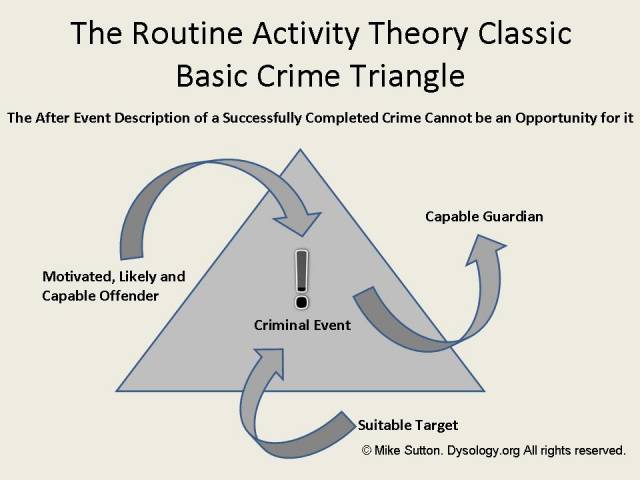

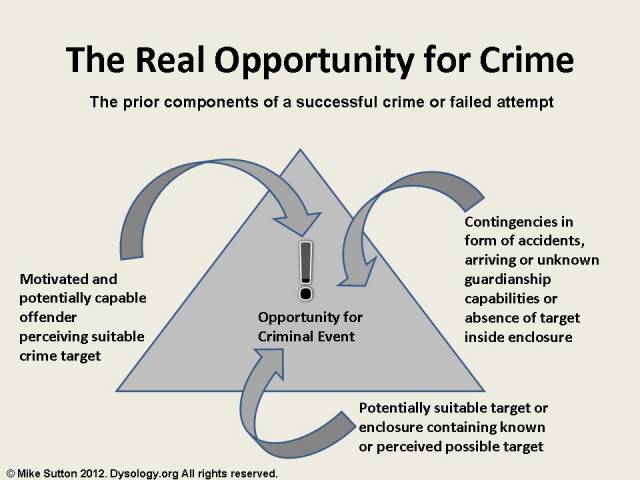

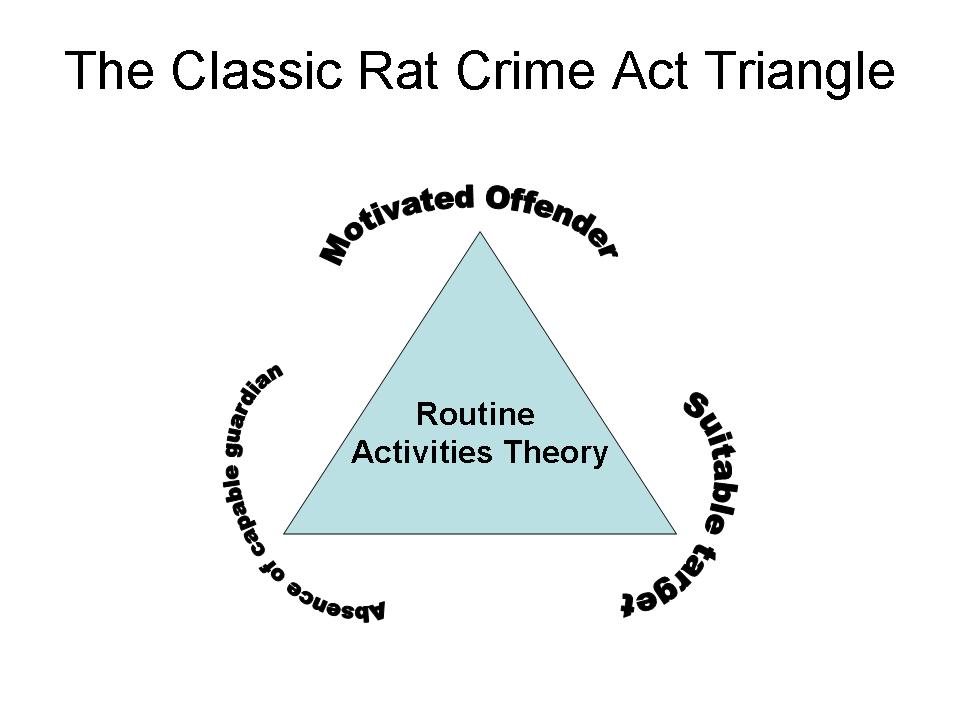

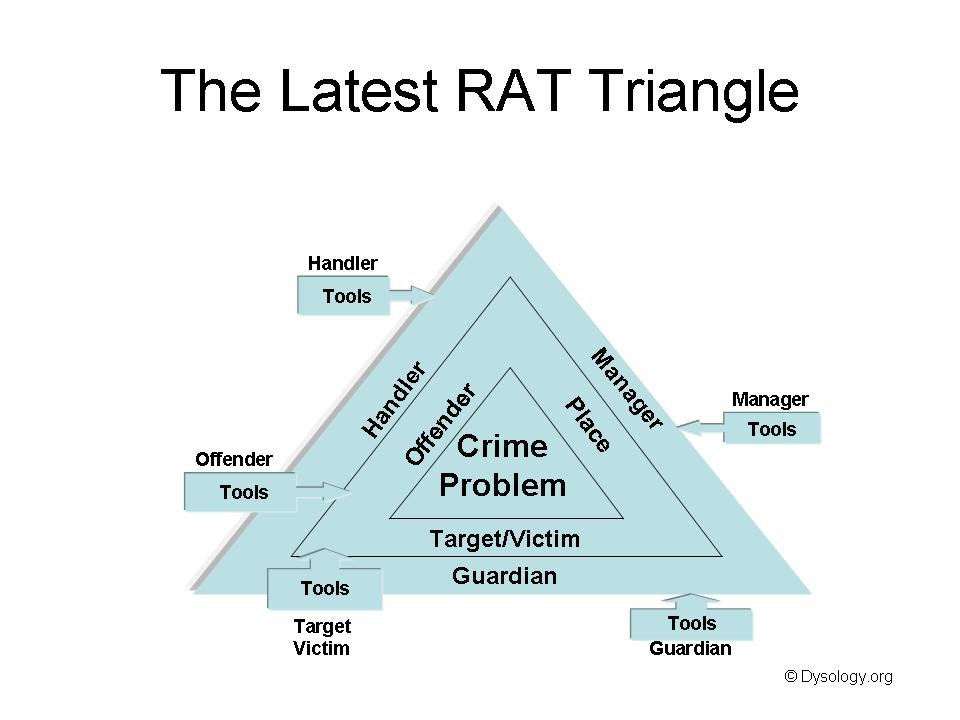

The following two diagrams show (1) the fallacy of Felson's classic RAT opportunity and (2) what a real crime opportunity is

(1) Currently accepted but fallacious "Ratortunity" notion of crime opportunity that can only exist after the crime is successfully completed.

(2) Veracious notion of a real crime opportunity as it exists before the crime is attempted

OFFENDERS PLAY DICE

Crime as opportunity theory and Routine Activity Theory are wrong, because these theories are based on the premise that the characteristics of a criminal opportunity are certain. Yet only once a crime has been unsuccessfully attempted, or successfully completed, are its offender and guardianship characteristics certain. Only then does the opportunity relinquish all its uncertainty.

My fourth peer-to-peer essay on crime and opportunity(Essay No 4): Contingency Makes or Breaks the Thief: Introducing the Perception Contingency Process (PCP) hypothesis is now published over at BestThinking.com This fourth essay proposes the way forward for Crime Opportunity Theories to avoid illogically and erroneously relying upon truisms as explanations for causality. And by placing motivation at the centre of the argument, the PCP hypothesis - if supported by empirical evidence in the field - might pave the way for a unified crime opportunity theory.

An updated and improved Essay no 3 ipublished on the BestThinking webstite: Opportunity Does Not Make the Thief

An interesting debate on the ratortunity myth can be joined by anyone on Linked[in] here

WHAT’S WRONG WITH RATORTUNTY?

Four thousands of years, in fact since the times of the ancient Egyptians and the ancient Greeks up until the late 19th century, the notion of the four humours of the human body formed the premise upon which orthodox medicine was practiced. It was a brilliant concept that was intuitively understandable by many, and it was compellingly simple and comprehensive in that it had universal applicability to all known symptoms and diseases. It was the rationale behind blood-letting as a treatment for a whole range of physiological and psychological problems. But it was completey wrong. The essays on this page of dysology are, as the heading says: On Opportunity and crime. In this work I question the rationality of the Routine Activities Theory (RAT) notion of crime opportunity and go on to disprove that it is a theory of causation. In this sense I am arguing that RAT is as wrong as the four humours notion of human physiology and that its recommendations are equally flawed in the extreme. By way of comparison, I argue that the ill-informed notion that poor physical security and guardianship is the most important cause of crime and that more physical security and guardianship the best answer to crime is sometimes as useless and harmful and sometimes incidentally slightly beneficial as bloodletting for illness. I then propose an alternative way forward for criminology to test proper hypothesis in order to build rational theories of crime causation that will inform crime reduction policymaking and policing.

The main question that drove me to explore this area is one that has been troubling me for some time, but that nobody else (as far as I am aware) has identified. Namely: How can the Routine Activities Theory notion of 'opportunity’ ( what I name ‘ratortunity’ for convenience) be a cause of crime when it's not a theory of causation but an irrefutable truism and description of the data?

The RAT crime triangle upon which much Crime Opportunity Theory and Crime Science is founded describes the elements of a successfully completed crime in commission. But how can something that you as an offender are described as being an absolutely essential part of, but have not yet become a part of, cause you to become a part of it? Obviously that’s not possible. And yet this irrational notion is accepted as veracious in criminology and crime science.

In the exploratory peer-to-peer essays below I reveal how ratortunity is based upon a simple truism and five fallacies. Weirdly, as the essays reveal, suported with lists of Harvard style references, Felson and Clarke (1998); Tilley and Laycock (2002); and Laycock (2003) all claim that their notion of 'opportunity' ('ratortunity' ) is not only a cause of crime but also that it is the most important cause of crime. This is something that is not only repeated in journal articles, book chapters, books and research reports - as though it is a rational and logical theory - it is also published in student textbooks.

One of the scholarship problems with Crime Opportunity Theory (which includes RAT, Situational Crime Prevention (SCP) and British Crime Science) is that crime opportunity theorists have a tendency towards collecting and reciting every scrap of confirming evidence while relatively disregarding the disconfirming evidence.

Theoretically, the main ratortunity problem is that the term "opportunity" as it is currently understood within criminology is the Routine Activities Theory (RAT) version (adopted by Situational Crime Prevention Theory, Crime as Opportunity theorists and UK Crime Scientists) based on Felson's classic crime triangle. Ratortunity is not at all the dictionary understanding of opportunity (essentially a convenient conjunction of circumstances upon which a person may choose to capitalise). Ratorunty is, irrationally, the notion that the essential elements of what is necessary for a successful crime to be completed presented themselves as a certainty in advance of the offender beginning to even attempt the crime. I explain in my arguments that this notion of ‘opportunity’ cannot possibly be a cause of crime – and suggest what my own proposed rational hypothesis of opportunity does comprise in my essay below on what I call the Perception Contingency Process (PCP).

I can't imagine any situations where the ratortunity notion could be a 'cause' of crime. In makng this criticism it is important to note that those who promote ratortunity as a cause of crime do not claim it is 'the' cause of crime (because they think ratortunity is a necessary but not a sufficient condition to be 'the' cause). Therefore Crime Opportunity Theorists claim ratortunity is 'a' cause.

Perhaps if an offender was able to know the future then it would be veracious to claim ratortunity is 'a' cause of crime. But if that was the case then an offender with such never before proven abilities would be more rational in their choices if they applied for the $1m James Randi Prize for proof of psychic ability rather than (for example) burgling a house. The reasoning here is that ratortunity is based on Felson’s Classic Crime Triangle which is nothing more than a post hoc explanation by way of a description of the data - not something that represents evidence to inform a theory of causality.

Many criminologists have criticised Crime Opportunity Theorists such as Felson and Clarke for the fact that they tend to take motivation as 'given'. Their relegation of motivation to the background of 'causality' is a long standing criticism of the theory. But Crime Opportunity theorists have always happily shrugged and lived with that. In more recent years both Felson and Clark have cited my work on stolen goods and the Market Reduction Approach on stolen goods markets and begun to consider opportunities for dealing in stolen goods and how demand and supply factors are important in terms of motivating people to steal . So this criticism is perhaps not quite as fair as it once was.

Perhaps a major problem we are going to have in convincing policy makers and policing services that the simple and compelling notion of ratortunity is actually complete claptrap is due to the way that the RAT triangle includes in one of its three elements 'capable/motivated likely offender'. Here, ratortunity theorists are not saying that ratortunities make all people into offenders. They believe instead that ratortunities are 'a' cause of some people committing crimes. They accept that there are complex social/cultural/economic ‘distal’ 'causes' of crime. They accept that but choose to focus on what they call 'proximal' (more immediate and 'environmental' factors) . Their goal is to try to make a difference in terms of crime reduction in the here and now - rather than some utopian future. That is fair enough. But the problem with ratortunity, is that offender capabilities (relative to guardianship) cannot be KNOWN in advance of each attempt.

Crime Opportunity Theory (RAT, SCP and Crime Science) is also based on the premise that Rational Choice Theory fits offender decision making so that they weigh up risks versus rewards in deciding whether or not to commit a crime. The problem is that this Rational Choice Theory premise does not square with the fixed in advance ratortunity notion of the crime triangle that is used to represent an 'opportunity' and a 'cause of crime, which – to reapeat the point already made -they argue is not only 'a cause' but also the most important cause of crime.

The Rational Choice Theory issue is dealt with by Crime Opportunity theorists saying , for example, that even where rationality is limited by such things as offending while suffering withdrawal symptoms or when intoxicated or when angry that (mental illness aside) rationality is bounded rationality. So what's rational according to Crime Opportunity theorists? It appears to be whatever they choose to decide to call rational because they see almost all offenders as rational to some degree. This is, of course, a separate criticism to my new criticism that ratortunity cannot be cause of crime.

Crime Opportunity theorist will happily admit that their theory is not so suitable for crimes of gratuitous violence. They promote it instead as the best theory for explaining high volume crimes such as theft and fraud. Hence Felson's popular book is entitled: "Crime and Everyday Life."

Routine Activity theory seeks to explain why crime occurs by explaining how changes in society bring victims and offenders together. A favourite example is that changes in society led to more women going out to work leaving more cars on the street as potential crime targets and more houses lacking capable guardianship containing more consumer durables worth stealing. They then use the RAT triangle to say that these changes in society represent an opportunity that is a cause of crime. So they do think they explain why crime occurs.

In sum, the fact that the RAT triangle cannot exist in advance of the crime being completed means they are wrong. What they need to develop is a theory of relative vulnerability that is testable and refutable. Anything else is pseudoscience

RAT is on the face of it a simple, initially plausible and compelling notion to latch onto - I can see why police services like it. But the very core of my argument here is that you have to move beyond simply ‘believing’ in something toward looking for veracious evidence. The only way to do that is by conducting proper research to test proper hypothesis in order to seek to build proper theories. To date the standard of research in this endeavour within the field of criminology has been dreadful. ( Just by way of example, check out how one of my undergraduate students found massive holes in the most highly publicised study of target hardening and crime reduction: http://http://www.internetjournalofcriminology.com/Phillips_Situational_Crime_Prevention_and_Crime_Displacement_IJC_July_2011.pdf

We should not forget that RAT theorists never invented security (target hardening etc). It’s not a new idea. People were building hill forts in Stone Age times. The Romans invented padlocks. Locks, guards, alarms etc. have been around since the dawn of civilisation - perhaps earlier. So what does ratortunity give us that we don't already know? Perhaps it gives us the right to believe that our beliefs are enough. This is of course a way of thinking that should have gone out with the Great Enlightenment that enabled science to inform knowledge. What got me looking at this issue is that Crime Opportunity theorists have now abandoned the social sciences and have re-badged themselves as Crime Scientists. I argue that they had better know what science is if they are going to do that. Hence my criticism of their failure to comprehend what science means by causality

What we need to know is why do targets that were once hard enough then become vulnerable?

This question turns us back to offender motivation. It also focuses our attention on risk and offender capabilities and their willingness to learn new skills. Why, for example might lead be safe on a roof for 40 years (when lead has always had a good scrap value in that period) and then suddenly become the hottest stolen product. Why are thieves electrocuting themselves trying to steal copper cable (which has always had a good scrap metal value) that was once protected sufficiently by risk of electrocution? The answer of course is the increased demand and extra cash now for scrap metal due to an increased demand from China. Google copper theft electrocution – you will see this is far from a rare event – both in the USA and across Europe.

So what degree of security are we going to have to impose on our entre way of life and infrastructure if we merely follow our instincts and beliefs and try to lock and nail everything down to the point that our way of life is ruined by fear of crime? I suggest a way forward for policing and general crime reduction and theory in two essays on my website (1) The Switching point and (2) The Perception Contingency Process here On Opportunity and Crime.

*****

Latest thoughts on Crime and Opportunity (12 April 20102) :

I was asked the following question, by email, today by an eminent Crime Scientist in relation to my criticism of the notion that ‘RAT opportunity’ (ratortunity) is a cause of crime: “…how would one's actions change if you configured the world a la Sutton as compared with a la Felson? I could enjoy any amount of outworking of that.”

Here is what I wrote by way of reply, which was by an email sent off the top of my head:

I partly agree and partly disagree. The question about how the world would be configured differently has two very distinct yet important parts (a) what it means for Crime Science , RAT and Crime Opportunity theory in general and those who work in the fields and (b) what it means for crime reduction.

I think that as a matter of intellectual principle we should not base our intellectual endeavours on absurdly irrational ideas. As you know, I believe the RAT notion of opportunity to be completely absurd. And think this holds true to a much more important degree if you are calling yourself a ‘scientist’.

With regards to the “so what?” question you raise. Let’s look at the possible implications (1) so what is the harm if we continue to confuse data with theory (1a) in regards to the issue of crime opportunities and (1b) any future work where we do the same because we have set a precedent that we feel this is OK to do in our discipline?

In terms of 1a I think because it 100 per cent fails to understand what causality is that those who believe it is a cause will use the Rat notion of opportunity as though it is causal and use that (wrongly) to look at underlining causes. The Felson World outcome = an obsession with security that will not pay-off in many areas (such as domestic burglary) and personal assault because the best locks in the world are useless if they are so cumbersome the door has to left ajar. And the most secure procedures in the world are useless if they are so life-inhibiting we would rather run the risk of victimization (Clarke has written about this himself) . But if ‘ratortunity’ is still deemed (wrongly) to be a cause and the most important cause of crime then where have you left yourself to go in terms of why you would want to address this problem by broadening your horizons from what you think (wrongly) to be the most important cause of crime?

As you can see 1a – shows how the world of Crime Science will be configured in a different way to other more rigorous scientific disciplines if you were to continue to think the RAT notion of ‘opportunity’ (ratortunity if you will) is acceptable. In effect, you are likely to be seen by everyone else as a bunch of pseudoscientists (based on Poppers definition). After all if you believe in ratortunity then what would stop you from making the same mistake again and again in other areas where you also confuse your data with explanations of your data unless you fez up to this early mistake and fix it in your work and teaching?

As we all know, security is nothing new – and yet Crime Opportunity Theorists with the Rat triangle underpinning a notion of causality are effectively telling themselves and everyone else that offenders commit crimes because they can . That’s pretty useless as an explanation that might enable mankind to identify areas for more effective intervention in a range of circumstances.

Ok so that’s the issue of how the world is likely to be configured one way or the other for Crime Scientists and others who believe in ratortunity.

We need next to ask: so how might this criticism of ratortunity actually be transfigured into some kind of crime reduction benefit over believing in it? Well it might help us to rationally decide where we wish to spend money on (a) security and (b) the various underlying causes of successful attempts made on that security. I think accepting that ratorunity is wrong is important and will make a difference because Crime Opportunity theorists (and the various national and local government departments, police organisations and others) would have to accept that guardianship and offender capabilities are perceptions (not fixed entities) in advance of successful and unsuccessful crimes. The three elements in the RAT crime triangle are perception of offenders – and where guardians are human they are perceptions belonging to guardians. Here then there is a whole new area to explore in terms of how different things impact upon perceptions to reduce crime and what the outcome is. Likewise for how perceptions cause crime to increase. It also means that we should no longer take motivation as ‘given’ and it also means that we need to explore how motivation (say an increase in the price of scrap metal) facilitates offenders becoming more likely or capable than they were before.

I write about this here: http://dysology.org/page8.html (scroll down to a piece entitled The Switching Point) and here: http://www.bestthinking.com/articles/science/social_sciences/sociology/contingency-makes-or-breaks-the-thief-introducing-the-perception-contingency-process-hypothesis

In a follw up email that day I wrote:

I guess the bone of contention is this: You and ****** and **** might have always considered ratortunity to be contingent ( re our emails last week – I sent you a couple of publications where you do write that) but (a) does Felson and does Clarke consider it to be based on perception or contingency? And if so where have they written that? Because I can’t find it.

And (2) more importantly – how has the ratortunity myth (identified by the scourge of Sutton ) been swallowed by others who have clearly not considered it to be subject to contingency and perception? And how, if at all, has that impacted on policymaking and teaching? This second point is something I am currently writing up – which is one reason why I was keen to make sure I was not being unjust (or just plain wrong) with regard to you ****** and **** .

*****

Papers here are published in reverse order (to get to the beginning you scroll to the bottom). This page of Dysology.org presents my thoughts over the past few months on the logical problems with the argument that opportunity is a cause of crime. These original arguments on this topic are currently being written up as a chapter for a book. The book focuses on the role of stolen goods markets as a cause of theft, other crimes such as violence and illegal drug dealing and - as a mere truism of course - the crime of handling stolen goods.

Essay No. 4: Contingency Makes or Breaks the Thief: Introducing the Perception Contingency Process Hypothesis

Crime Opportunity Theory is wrong in arguing that 'opportunity makes the thief", and that opportunity is "…the single most important cause of crime." This article proposes a more promising hypothesis for policing and crime reduction that is intended for testing in the field.

Please note that an updated version of this essay is published on the Best Thinking website: click here

Introduction

Three essays on crime and so called criminal ‘opportunity’ are published on my website Dysology.org (Sutton 2011, 2012a). See: Opportunity Does Not Make the Thief (Sutton 2012) for an overview. In those essays, I explain in detail why, with one exceptional reinterpretation (Farrell et al 1995), the Routine Activities Theory (RAT) notion of opportunity is a truism that has been overcomplicated and dressed up as a theory of crime causality. In those earlier essays logic is used to reveal that RAT ‘opportunity’ is no more than a very precise description of the data of any successfully completed crime in commission, which is something that can only be known after the event of its successful completion.

In this fourth essay on crime and opportunity, I propose a new way of understanding crime opportunity that puts motivation at the centre of a process that is larger than the traditional focus upon the crime act. This new way of understanding crime opportunities might provide a potential route to a unified theory of crime. Firstly, however, I make the argument that the next task for criminology, if it is to move forward from mistaking simple truisms about the data of crimes as hypotheses and theories to explain that data, is to collect and examine many examples from case studies that represent disconfirming evidence for the usefulness of the RAT crime triangle. By doing this we can see exactly why it is not only logically wrong, but also the extent to which it has been seriously misleading criminologists and policy makers by claiming that the RAT notion of ‘opportunity’ is a cause of crime. To provide an example of how useful this approach might be, one specific example of disconfirming evidence for RAT opportunity is discussed next.

An untypical burglary dramatically reveals how offenders’ perceptions are part of a process that is contingent and equally applicable to the mundane reality of everyday crimes.

Let us consider some rather unusual and dramatic crime evidence from Nottingham in the UK, which enables us to see in stark detail exactly why the RAT Crime Triangle cannot be used to explain what happened in one particular case. The particular example of disconfirming evidence that I am about to reveal gets the point across very dramatically. However, the same logic, which is briefly set out here and in more detail in a number of other essays (Sutton 2011, 2012, 2012a), shows that Crime Opportunity Theory is wrong for all crime. And that means it is equally wrong in terms of explaining the causes of commonplace and oftentimes more mundane crimes that Crime Opportunity theorists believe the RAT Crime Triangle and its associated theory are most suited to explaining.

The following news report is from the front page of the Nottingham Post (Howell 2012):

‘A Father who killed a burglar by attacking him with a meat cleaver was “justified”, a Notts coroner has ruled.

Steven Shaw and his brother Craig broke into a house in Morrell Bank on the Bestwood Estate in March 31 last year.

In a “harrowing and brutal” attack, which lasted between 10 and 15 minutes, they assaulted taxi driver Xiaopeng Wang and his wife, and also left the couple’s baby injured.

The violence only stopped when Mr Wang found a meat cleaver and hit Mr Shaw with it, causing a “sharp force trauma” to his head.

At Mr Shaw’s inquest yesterday, Notts Coroner Mairin Casey recorded a verdict of lawful killing and said: “The defensive action taken by Mr Wang was proportionate and justified.

“This was a harrowing and brutal experience for all of them, and I understand they are still traumatised.”

She also said that the attack was “random” – the Shaw brothers had never before met the Wangs – and that the motive for the break-in was a financial one.

The court heard that Steven Shaw, 32, originally from Cedar Road Forrest Fields, punched Mrs Wang in the face and she was forced to watch as her husband was assaulted.

Toxicology reports found traces of cocaine and alcohol in Mr Shaw’s bloodstream.’

We can examine whether or not the Classic Rat Crime Triangle can help us to understand the ‘cause’ of this particular crime.

Figure 1.

The triangle in Figure 1 depicts the RAT explanation for Opportunity Theory’s notion of opportunity as a cause of crime. According to RAT, crime is thought to be ‘caused’ by the coming together of (1) motivated ‘likely’ capable offenders, (2) a target that they deem suitable and (3) the absence of a capable guardian against them.

It seems reasonable that Nottinghamshire’s Steven Shaw and his Brother Craig Shaw, and their getaway driver Daniel Miller (See: Howell 2012, p.3) perceived the Wang family to be relatively incapable guardians of themselves and their home. Had the Shaw brothers and their accomplice managed to complete their crime successfully then the RAT crime triangle would have provided a post-event record of the essential data of the successful crime act in commission. However, since they were thwarted from completing the burglary to their planned script, their initial perception of the guardianship capabilities of Mr Wang proved wrong. And yet Mr Wang and his family were both criminally assaulted and burgled. So does the fact that they were incapable guardians, until the point at which meat cleaver was used in self-defence, explain why the Wang home was burgled and the family assaulted? Up until the point when Mr Wang used the meat cleaver to fight back, the Shaw brothers were the capable offenders and the Wangs were incapable guardians.

What if Mr Wang had chopped off the hand of the first of the Shaw brothers coming in through his window or door? Or what of the fact that Mr Wang was not standing outside his own home swinging a meat cleaver? Does his armed absence from the front of his house prove that the reason the house was burgled in the first place was because the Wangs were incapable guardians of the outside of their home?

What if Mr Wang had gone further and also killed Craig Shaw with a cleaver blow to the back of the head as he tried to leave the house? If that had occurred, it is quite likely that Mr Wang would have been found guilty of using inappropriate force. Could such a crime of manslaughter then be explained by the fact that the Shaw brothers were incapable guardians against the motivated and capable householder Mr Wang?

From this news story of a real, if somewhat unusually dramatic, burglary we can see that both the guardianship and offender capability elements of the crime triangle can be known only after the crime has been successfully completed. Therefore, the RAT Crime Triangle depicted in Figure 1 cannot logically be used to make the claim that this notion of ‘opportunity’ is a cause of crime. And yet that is exactly how Crime Opportunity theorists currently use it.

So what might be a better way of thinking about crime opportunities?

I propose that the best way forward for Crime Opportunity Theory is to consider criminal events as something much larger and detailed than the act with which the law concerns itself. Nottinghamshire's Shaw brothers and their getaway driver, like all offenders, were following a crime script that necessarily contains impromptu characteristics. The crime script for the burglary of the Wang’s home could be read from the moment they awoke to the death of Steven Shaw. Such crime scripts are a process involving a sequential chain of discrete actions informed by offender perceptions of target value and relative vulnerability. Each discrete action has an intended outcome but is always shadowed by possible unintended outcomes. We might call this the Perception Contingency Process (PCP).

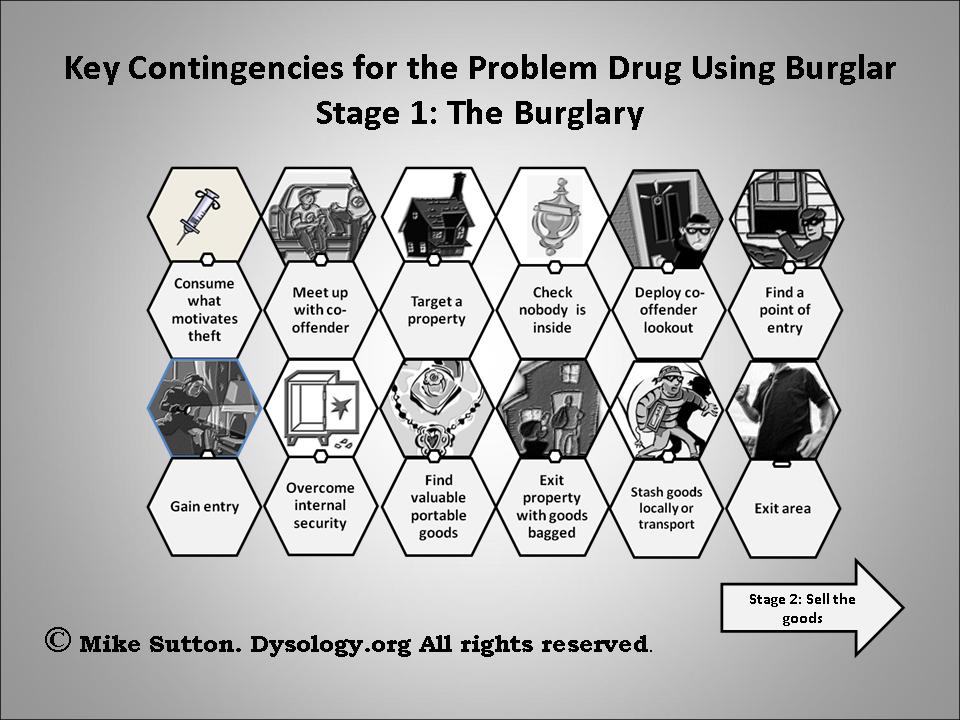

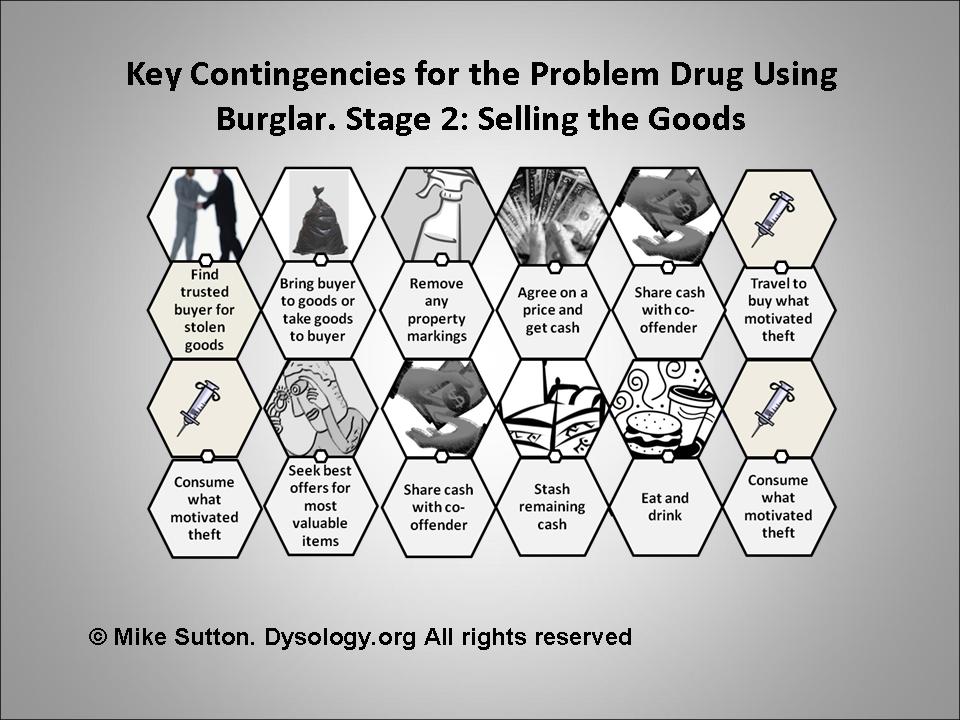

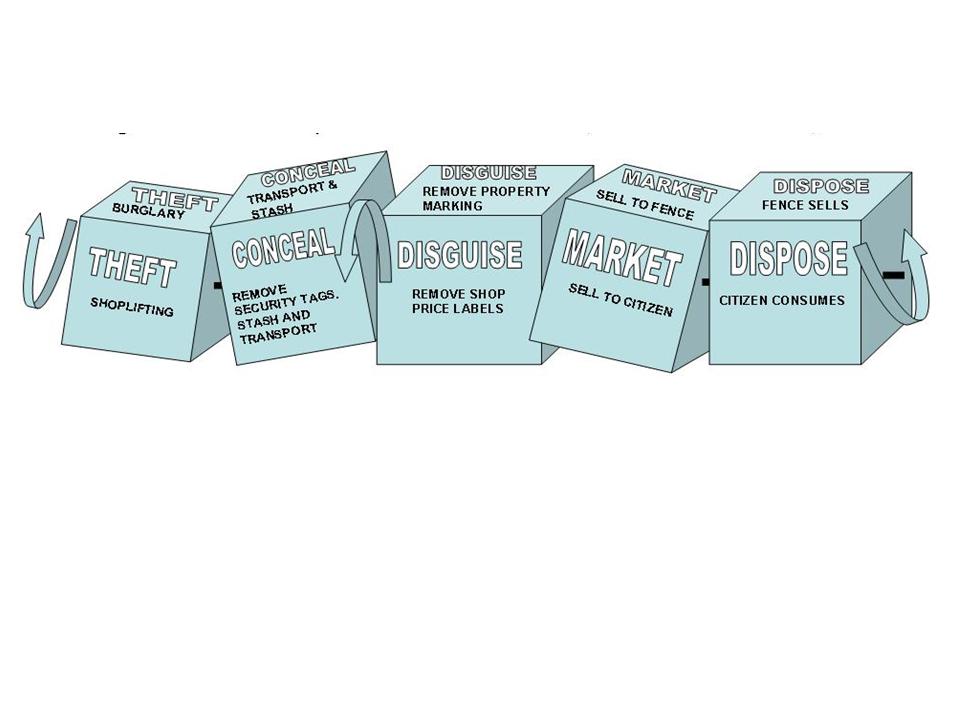

Figures 2 and 3 below are simple informatics that describe the proposed Perception Contingency Process from the point of view of a typical problem drug using burglar. Based on less dramatic events than those involved in the Shaw brothers burglary of the Wang's home, these more typical crime scripts are exemplars that depict the necessary objectives that thieves need to complete as part of a wider process surrounding typical domestic burglaries. The two figures reveal this wider process by showing that the thief’s concerns, and his need to 'safely' complete a series of objectives linked to those concerns, is something that begins before and extends beyond the precise act of burglary, or attempted burglary.

Figure 2

Figure 3

One of the reasons why the RAT crime triangle is so unsuitable as an explanation for crime is that it is essentially concerned with the same essential legal focus upon of the scene of the criminal act itself.

Alternatively, the informatics in Figures 2 and 3 provide just one example from what is likely to be a more useful account of the larger number of alternative and ever-evolving scripts held by active prolific offenders. These two informatics are based upon over 100 in-depth qualitative interviews that I have conducted with prolific burglars and other thieves over the past 20 years. Consequently, in this essay they are merely a pastiche created to demonstrate what a typical burglary crime script tends to involve. Each of the 24 hexagons contained in Figures 2 and 3 represents an individual objective. Each objective, until it is successfully completed, is shadowed by unforeseen events (for example: such as householders unexpectedly wielding meat cleavers). If the problem drug using burglar depicted in Figures 2 and 3 is unable to complete any one of these 24 objectives then his main aim of taking drugs and avoiding detection that day is thwarted. For example, he may have to go out and steal before he can take his first drugs of the day because he was unable to keep enough stashed for the morning. Such a start to the day is very risky. To begin with, doing a burglary while 'clucking' - to use the street vernacular - is known to be extremely unpleasant for the offender. It is also high risk because less care is taken at such times of desperation. And selling stolen goods in such a state brings further risks to stolen goods dealers who should not be seen trading with obvious twitchy ‘smack-heads’. Other things can go wrong. For example, in the event of a householder returning home the burglar's lookout might flee the scene without raising the alarm. Or he might sneakily return to steal the stash of stolen goods for himself. The burglar may be arrested in possession of the stolen goods while transporting them to the point of sale. Or he may be stopped in his tracks by people to whom he owes money and lose his drugs money. Given that any number of things can go wrong in the course of the crime script, the PCP Crime Opportunity hypothesis, is that: contingency makes or breaks the thief. The crime reduction hypotheses that follows is that intervening in any one of a multitude of typical key offending objectives in order to load the dice against offenders might work to reduce crime rates.

It isproposed that crime scripts have key common features that enable us to generalize about individual offenders. However the number and type of objectives in crime scripts will vary between different types of offence as well as between different offenders committing the same type of offence. Different motives will have different objectives. And what happens in the course of a crime script will most certainly shape it. For example, if a burglary haul is not particularly lucrative then the problem drug using burglar will try to commit another burglary, or perhaps go shoplifting, in order to get enough money to the buy the drugs he wants to consume. Unlike Felson's RAT crime triangle, crime scripts are necessarily dynamic. And it is this dynamic property that provides potential for crime reduction through disruption of the PCP.

Crime scripts will usually overlap with those of other offenders. This is obvious in the following examples: the burglar and his lookout, the burglar and his fence, the fence and the final consumer, and the burglar and his drug dealer and the drug dealer and all his custmers and co-offenders.

The PCP focus upon the offender's main aim seems compellingly sensible in the case of the problem drug using burglar. In other cases it may be less apt. For example, what of the wealthy gangster? What is his main aim for dealing in drugs? Is it to stay alive in his own neighbourhood? Is it to wield power and influence? Is it to bully others? Is it to attain further wealth? Are any of these inseparable from staying alive in his own neighbourhood given his history?

Motive is important, and there may be multiple motives, and seeking to better understand how motives match aims and objectives is where further research is needed. Meanwhile, each typical objective and possible contingency in the particular crime process we are interested in allows us greater potential to see that there are many possible areas where crime reduction and police work might aim to intervene to prevent an offender from achieving the main aim that motivates their offending.

Seeking to better understand each typical objectve and possible contingency in the particular crime process we are interested in allows us greater potential to see that there are many possible areas where crime reduction and police work might aim to intervene to prevent an offender from achieving the main aim that motivates their offending.

Nothing is certain, nothing ‘known’ until the contingency is over

Crime as opportunity theory and Routine Activity Theory are wrong, because these theories are based on the premise that the characteristics of a criminal opportunity are certain. Yet only once a crime has been unsuccessfully attempted, or successfully completed, are its offender and guardianship characteristics certain. Only then does the opportunity relinquish all its uncertainty. Up until that point, offenders are rolling the dice. They might think those dice are loaded in their favour, sometimes they might think the opposite and still attempt the crime. But they never ‘know’ how the dice might bounce and land.

Discussion, Conclusion and the Way Forward

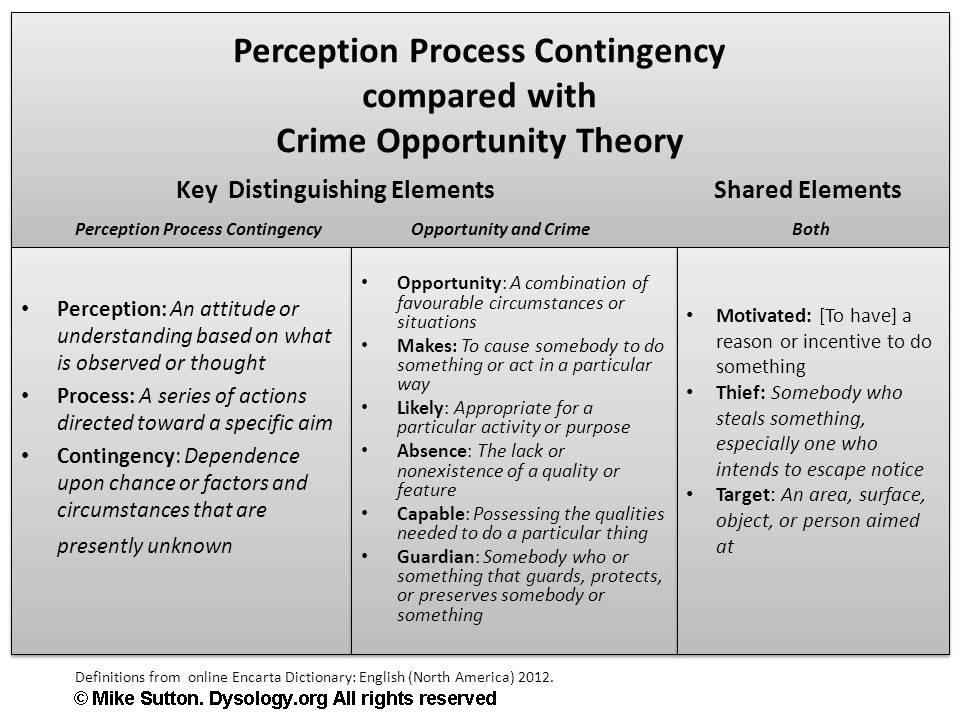

Figure 4 below shows the key differences between the proposed PCP and current RAT based Crime Opportunity Theory. The essentially difference is that PCP reflects the reality of the uncertainty of crime, whereas Crime Opportunity Theory is currently based on the illogical and weird premise that successful criminal outcomes cause themselves to happen because they exist before the crime is completed and that offenders can perceive such certainties and so act upon them.

In the interests of absolute clarity, Figure 4 shows also the essential similarities of agreed definitions between PCP and current Crime Opportunity Theory.

Figure 4

Because Crime Opportunity Theorists have typically sought to support rather than disprove their hypotheses they have relied heavily upon unapt examples, such as gas suicides and motor cycle helmet legislation (Sutton 2012), to support their beliefs, whilst paying scant regard to the needs of sound scholarship with regard to purposely seeking out disconfirming evidence. For this reason we must seek to redress the balance. From that cause, and by way of example of what is needed, I provide two more examples in this essay that show why opportunity is uncertain until after the crime is successfully committed. Both are taken from the same edition of the newspaper that reported on the Shaw brother’s aggravated burglary of the Home of the Wang family. Both show how, to varying extents, the offenders crime scripts did not go quite to plan when their perceptions of relatively incapable guardianship were controverted. Firstly, page 4 of the Nottingham Post, March 27th 2012 reports on another burglary involving a meat cleaver:

‘Police are appealing for information to help trace a knife-wielding burglar.

The offender was with Jason Fisher, who was caught at a house in Ednaston Road, Dunkirk, just after midnight on Friday, February 24, carrying a meat cleaver.

Students living in the house disarmed the 27 year old, sat him down in a corner and hemmed him in with chairs until police arrived.

…A second offender, who was carrying a knife as the pair entered the house fled the scene and has not been traced.’

Secondly, page 7 reports on yet another burglary:

‘Two rings were stolen after a thief climbed through a into a house in Wollaton.

The incident happened at around 8.20pm on Wednesday March 14. The suspect escaped with two rings when he was disturbed by residents.’

We need now to move forward by collecting and examining the properties of many more case studies of disconfirming evidence for the RAT notion of crime opportunity that currently underpins all Crime Opportunity Theories. This exercise is important because the simple and compellingly attractive, yet completely illogical, notion of RAT ‘opportunity’ is currently central to much crime reduction policy making and policing.

Merely concerning ourselves with the properties of action that fulfils the legal criteria for different offences (as RAT ‘opportunity theory’ has done to date) hinders our understanding of all offences and how we might better seek to reduce them.

Offenders operate by means of crime scripts (Cornish 1994; Sutton 2010) that involve a process with an aim and a linked series of objectives involving actions, some intrinsically legal, some not. These scripts all begin before and continue after a particular crime act. Opportunities for crime might be understood more accurately, therefore, if we focus our attention upon how offenders’ main daily aims are dependent upon their personal perceptions of a number of linked situations that are each, in turn, shadowed by contingencies. Here, there is likely to be new potential for crime reduction and policing to be informed by new empirical research to develop and experiment with new ways of reducing crime across the board by seeking to thwart individual criminal objectives in order to deny offenders their main aims – such as consuming illegal drugs – which motivate them to offend.

The ‘Opportunity’ Myth has had a significant impact on policing and crime reduction policy making. Because the RAT notion of crime 'opportunity' as a cause of crime is widely supported by both the British Home Office and the US Department of Justice (e.g. Parliament UK 2010; US Department of Justice 2012) . Such dominant support has undoubtedly focused policing and crime reduction attention upon crime scenes that are immediately related to the crime statistics that these governments are aiming to reduce. This must, inevitably and systematically, divert policing attention from the wider and more complex offender objectives that are intrinsically involved in offending as a wider process.

If we take domestic burglary as just one particular example of what this tight focus on the crime scene has led to, we can see that the current focus has inevitably resulted in an official preoccupation with household security improvements at burglary scenes. Hence, there has been a policing and government good practice preoccupation with crime hot spot analysis, locks and bolts, alarms, property marking, forensic investigation, repeat victimisation and the establishment of neighbourhood watch programmes in areas with high rates of burglary. The problem with this is that the recommended solutions have been heavily preoccupied with the crime scene and technique effectiveness is known to be necessarily limited. For example, security improvements are often dependent upon (1) the ability of potential victims to pay for them, and (2) security as an idea about what to do about crime does not really offer the public very much that is new that they are not already aware of. After all, locks and bolts and alarms of various types have been around for thousands of years. These devices were not invented by governments or police services. So nothing intrinsically new and necessarily more effective in the long term is on offer here.

We know that after decades-long evolutionary arms races between technology and offending techniques that involve target hardening things like parked cars and banks and bank vaults and security vans does eventually significantly reduce robbery and theft of certain targets. The problem with domestic burglary, however, is that ordinary people are not dwelling in banks, cars or security vans. If people are to enjoy some semblance of a normal existence they will often need to leave their homes unoccupied, their windows open, alarms off, doors and windows unlocked and valuable goods within plain sight of windows. To live without fearful obsession, people need to limit the amount of time they spend each day securing and capably guarding their possessions against the possibility of theft. Moreover, neighbourhood watch has never been even remotely proven to be effective at reducing crime; although administrative criminologist sometimes tie themselves up in knots trying their very hardest to explain how it might work if only it did (e.g. Laycock 2001) and neither has any kind of property marking ever been proven to reduce theft (Sutton 2010).

Ultimately, what I am proposing in this essay is that we need to think outside the crime scene box, as well as within it, in the same way that offenders think and organise their wider offending. Counterintuitively, therefore, we should pay much greater attention to the interconnected objectives and main aims of offenders that reside outside of the actual criminal acts we are trying to reduce.

One of the major criticisms of Crime Opportunity Theory, particularly its RAT and Situational Crime Prevention elements (e.g. Haywood 2007), is that it takes offender motivation and wider cultural issues for granted. PCP, however, takes motive into account and sees it as central to opportunity as a contingent process. Therefore, PCP provides a potential means to examine, explain and better understand crime opportunities in a way that might allow critical criminologists, 'administrative criminologists' and 'crime scientists' to work toward a unified opportunity theory of crime causation and reduction.

References

Farrell, G. Phillips. C. and Pease, K. (1995) Like Taking Candy: Why Does Repeat Victimization Occur? British Journal of Criminology. Vol. 35. Summer. pp. 384-399

Hayward, K. ( 2007 ) Situational Crime Prevention and its Discontents: Rational Choice Theory versus the ‘Culture of Now’ Social Policy and Administration. Vol 4. No. 3. 232-250

Howell, D. (2012) Killing Thief With Cleaver Was Lawful: Coroner’s verdict after dad fought raiders in his home. Nottingham Post. p.1 (and p.3).

Sutton, M. (2011, 2012a) On Opportunity and Crime. Dysology.org. http://dysology.org/page8.html

Sutton, M. (2010) Stolen Goods Markets. Problem Oriented Policing Guide No. 57. U.S.A. Department of Justice COPS Programme. (Peer reviewed international policing guide. http://www.popcenter.org/problems/stolen_goods/

US Department of Justice (2012) Crime Analysis for Problem Solvers in 60 Small Steps: Know that Opportunity Makes the Thief (2012):: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. Cops Programme, Centre for Problem Oriented Policing.http://www.popcenter.org/learning/60steps/index.cfm?stepNum=9

Essay No. 3: Based As It Is On Simple Truisms And Five Fallacies - Equivocation, Ambiguity, Precognition, Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc, and the Social Absolute - Crime as Opportunity Theory As A Cause of Crime is Currently Wrong: Proposing Some Ways Forward

The Future has many names

For the weak it is unattainable

For the fearful it is unknown

For the bold it is opportunity

*

Victor Hugo

The RAT notion of opportunity has many names

For the opportunity theorist it is causality

For the guardian it is incapacitation or absence

For the thief it is precognisence

For the philosopher it is truism

For the crime 'scientist' it is brilliant

For the dysologist it is remarkable claptrap

For the scientist it is pseudoscience

*

Mike Sutton

This essay seeks to get to grips with what I see to be the barrier to crime reduction knowledge progression that has been thrown up by two criminology theories/approaches: Situational Crime Prevention (SCP) and Routine Activities Theory (RAT). This problem is caused by the policy oriented popularity of SCP and RAT that is likely due in no small part to their simplistic and easily comprehendible, compelling, yet ultimately illogical weird focus upon describing the data of crime in ever more complex ways so that simple truisms about the scenes of crime and potential crime are placed in the spotlight and presented as a root cause of crime . Yet, as this essay reveals, this notion of opportunity is in fact the very data that a true testable theory of causation could explain.

My concern with the need to fully understand the criminological notion of opportunity and to examine claims that ‘opportunity is a cause of crime’ stems from the fact that many key academic proponents of the Situational Crime Prevention (SCP) approach, and Routine Activities Theory (RAT) – who have been collectively labelled Administrative Criminologists (Young 1994) – are now claiming to be scientists working in the mould of natural scientists under their own self-styled designation as Crime Scientists (Laycock 2003; Pease 2008) and claiming that their notion of criminological opportunity is the most important cause of crime (Felson and Clarke 1998; Tilley and Laycock 2002; Laycock 2003).

My identification of logical problems with the RAT notion of opportunity caused me to conclude that it is not a scientific explanation for causality, but is instead a mere truism. This issue is addressed in depth in Essays No 1 and No2 (below), on this page. The essential argument made so far on this page of Dysology.org is that the RAT notion of crime opportunity - described as an 'opportunity theory' by its own author, and by the originator of SCP, Ronald Clarke (e.g. Felson and Clarke 1998: p. v), is pseudoscientific (Popper 1976) because it is a truism that is incapable of empirical testing and falsification.

Note: The basic problem is that the RAT notion of opportunity for crime is based on the Classic RAT Triangle that describes the essential elements of a successfully completed crime only (see Fig 1). But what of all those perceived opportunities that don't work out for the offender? Illogically, the RAT notion of opportunity is based on information that nobody can know until after the crime is successfully completed.

This third essay on crime and opportunity seeks to understand the reasons why RAT, SCP and Crime Science , and their critics, failed to identify this problem. I conclude in this essay that the reason they all failed to spot it seems to be based on a failure among crime as opportunity theorists to clearly and consistently define what they mean by opportunity or by guardianship.

The Fallacy of Equivocation

Equivocation is a logical fallacy that occurs when the same term is used in different senses in order to make an argument. An example is: "The water vole lives in the bank. Banks are found in city centres. Therefore, the water vole lives in the city centre."

Dictionary definitions of opportunity generally describe it along the lines of being a favourable appropriate or advantageous juncture of circumstances. Unless the simple truism nature of the RAT trinity is explained (and it never is) the use of the word opportunity is naturally taken by the reader to mean that it is something that occurs before the crime takes place - and so is a cause of it. But as Essay No 1 (below) on this web page explains, the RAT, SCP and Crime Science notion of opportunity is something that only occurs for sure after the crime has been successfully completed. Therefore, I would argue that the claim that opportunity is a cause of crime is an example of the fallacy of equivocation.

Some who claim that opportunity is a cause of crime have gone further to claim that it is the most important cause of crime (Tilley and Laycock 2002). To repeat the point already made, their notion of opportunity as a cause of crime is not the simple and commonly understood one for opportunity in general, which consists of a favourable, appropriate or advantageous juncture of circumstances existing prior to any action that might capitalise on it; rather it involves three things coming together in time and place after the event: (a) a suitably motivated and capable offender (b) a suitable target for that offender and (c) the absence of capable guardianship to protect the target from the offender (Felson and Boba 2010). We might call these three things the RAT trilogy. Those who argue for the theory of "opportunity as a cause of crime" do not explain that what they mean by opportunity is a description of what they can only know to be these three core components of a successful crime in commission after it has happened (not during, and not before) because that is the only way that they know for sure that the offender was capable of overcoming the guardianship. That alone is enough to prove that crime as opportunity theory is an example of the fallacy of equivocation because those who use the RAT 'after the event' trilogy of 'crime as opportunity' argument fail to make it clear that it does not mean the universally understood and more commonly understood notion of opportunity as something that occurs prior to an act that capitalises on it.

The Fallacy of Ambiguity

The philosopher Gary Curtis (undated) writes: “Because of the ubiquity of ambiguity in natural language, it is important to realize that its presence in an argument is not sufficient to render it fallacious, otherwise, all such arguments would be fallacious. Most ambiguity is logically harmless, a fallacy occurring only when ambiguity causes an argument's form to appear validating when it is not.”

Accepting Curtis’s definition of the informal logical fallacy of ambiguity in arguments, we can apply it to the argument that opportunity is a cause of crime in order to determine (a) whether it is used ambiguously and (b) whether that ambiguous use is sufficient to render the argument fallacious.

To proceed, it seems useful to first seek to establish what is commonly and most widely understood by the word ‘opportunity’ . As Garwood (2011 p.37) points out:

“The Merrian-Webster Online Dictionary defines opportunity as ‘a favourable juncture of circumstances’. In common with many such definitions, this excludes consideration of the mindset of the person faced with such a juncture of circumstances.”

In this essay we will see that the current criminological notion of opportunity as a cause of crime goes way beyond this commonly agreed dictionary definition. The criminolological notion of opportunity as it currently stands includes not only the mind of the potential criminal actor but, amongst a host of other complexities, also the intrinsic incapability or actual failure of others, (a) present or (b) not even present, to prevent the crime. Most importantly, such information can only be known for sure after the crime was successfully accomplished.

Ambiguity about the RAT concept of guardianship causes further ambiguity about whether opportunity is a refutable scientific explanation or merely a description of the data of a successfully completed crime that amounts to a mere truism.

The RAT notion of opportunity incorporates the need to understand what actually happens before, during and after a crime. This goes beyond the common understanding from dictionary definitions of opportunity as being perceived as circumstances favourable to a perceived goal that the perceiver can choose to capitalise upon or pass up. As Felson (1986) explains at length:

To understand criminal opportunity, we need to know not only some of the decisions made by offenders, human targets, guardians, and handlers, but also the situations of their physical convergence as a result of these decisions, regardless of whether the decision makers know what we, as analysts, know. And we have to know the outcome. Was the offender wrong, missing a golden opportunity or committing a silly blunder? Did the getaway car stall or did the selected target trap him? Did the victim succeed by going through the day safe from crime, regardless of whether he or she thought about it? What choices on the part of a citizen produce an unplanned victimization and impair or assist guardianship of targets and handling of offenders? Indeed, a criminal situation is made possible by various decisions by those who set the stage for the convergence of the four minimal elements, however inadvertently. Any set of decisions that assembles a handled offender and a suitable target, in the absence of a capable guardian and intimate handler, will tend to be criminogenic. Conversely, any decision that prevents this convergence will impair criminal acts. Even though an offender may prefer to violate the law, his or her preference can be thwarted by the structure of decisions made by others, regardless of whether they know they are preventing a crime from occurring. In short, we cannot understand the rational structure of criminal behavior by considering the reasoning of only one actor in the system.'

Tilley and Laycock (2002) similarly perceive the criminological notion of ‘opportunity’ as inseparable from the rewards of successful offending:

‘The most significant, and universal cause is, however, opportunity. If there were no opportunities there would be no crimes; the same cannot be said for any of the other contributory causes. In so far as opportunity creates criminality by rewarding those with low motivation with success in easily chosen and completed crime, it thus comprises a root cause - as one recent paper puts it, ‘Opportunity makes the thief‘ (Felson and Clarke, 1998).’

Clarke (1984) and Felson and Clarke (1988) see the RAT explanation for crime as integral to the notion of Crime Opportunity Theory. Despite routine use of the word 'opportunity' in their work these authors fail to make it clear what they mean by it. Instead they are opaque and mysterious about what they really mean, exactly, by 'opportunity'. This might even stem from their personal uncertainty. Consider the following fogginess from Clarke (1984: 80):

'The difficulties of achieving the necessary accuracy in counts of criminal opportunities derive in large part from the conceptual complexities; opportunity is not merely the necessary condition for offending, but it can provoke crime and can also be sought and created by those with necessary motivation.'

Felson and Boba (2010) similarly fail to define with any degree of clarity what they mean by opportunity. Consider the following vagueness (p206) which seems that it might mean to imply that the RAT trilogy notion of the core components of a crime are part of what is integral to the meaning of opportunity. Although it fails to appreciate the reality of much crime where offenders offend on foot and travel to the crime scene on foot and do not rely on transport to sell what they steal:

'Crime is a process, depending on the convergence of offenders and targets in the absence of guardians. The transportation system generates these convergences. Markets for stolen goods are of central importance for generating crime opportunities, and opportunities make the thief.'

The problem is that criminologists who support opportunity theories of crime have not produced a clear or consistent definition of the criminological meaning of opportunity (See e.g. Willison 2000; Garwood 2011). The reasons for this lack of a succinct definition are very clearly stated by Clarke (1984). While never clearly defining opportunity himself, Clarke distinguishes between many types of situations and targets for crime that he loosely describes as criminal opportunities. For example, he writes about subjective assessments made by potential criminals of the ease and attractiveness of opportunities. He then mentions the fact that some offenders go hunting for opportunities, while others manipulate the world so as to create them or plan for them when they occur. He says that some opportunities relate to routine activities or the situations in which crimes take place and to differential vulnerabilities of targets and differential attractiveness between targets . Clarke ultimately concludes that it would be extremely difficult to quantify opportunities in society due to these conceptual difficulties. This presents a problem for crime science if, as Laycock (2003) writes, it is to be founded on the premise that opportunity is a cause of crime. We can see from Felson's (1986) attempt to explain the complexity of his notion of crime opportunity, and from reading Clarke's (1984) paper, that the notion of opportunity as a cause of crime is a complex idea in need of an equation.

Clarke's own failure to get to grips with a clear definition of what he means by opportunity is a good example of the fact that we must always bear in mind, when considering arguments that opportunity is a cause of crime, that those who believe this consider opportunity to be many different things and this makes their notion of it not only very complex but also very ill-defined, which results in its idiosyncratic usage in ambiguous arguments - such as (Felson and Clarke 1998 p. v: '...opportunity is a root cause of crime.' My contention that this argument is ambiguous is something that the remainder of this paper seeks to demonstrate.

To compound this problem, Felson is also ambiguous about the meaning of guardianship. On page 28 of his fourth edition of Crime and Everyday Life (Felson and Boba 2010) the author’s write that the third almost always’ element of a criminal act is: ‘The absence of a capable guardian against the offence.’ Their notion of guardianship is that it must be capable only twice - on pages 28 and 47. Elsewhere in the book (pp. 30, 31, 32, 33 and 180) on five different pages the presence of a person is sufficient to make them a guardian that may deter crime (note Felson and Boba do not say it will in all cases) – there is no mention of them needing to be capable. Criminology geeks might be interested to learn that in the third edition of Crime and Everyday Life (Felson 2002) Felson uses the term ‘capable guardian’ three times (pp. 21, 35, 79) and ‘guardian’ alone three times. Both terms are used by Felson (And Felson and Boba) as though they mean the same thing. But, as this essay will show when explaining Fig 2 (below) there is a world of difference between what these two phrases actually mean.

Felson's basic and classic Routine Activities Triangle is used by countless academics, police and government departments to guide their understanding and crime policy making (e.g. Anderson 2010).

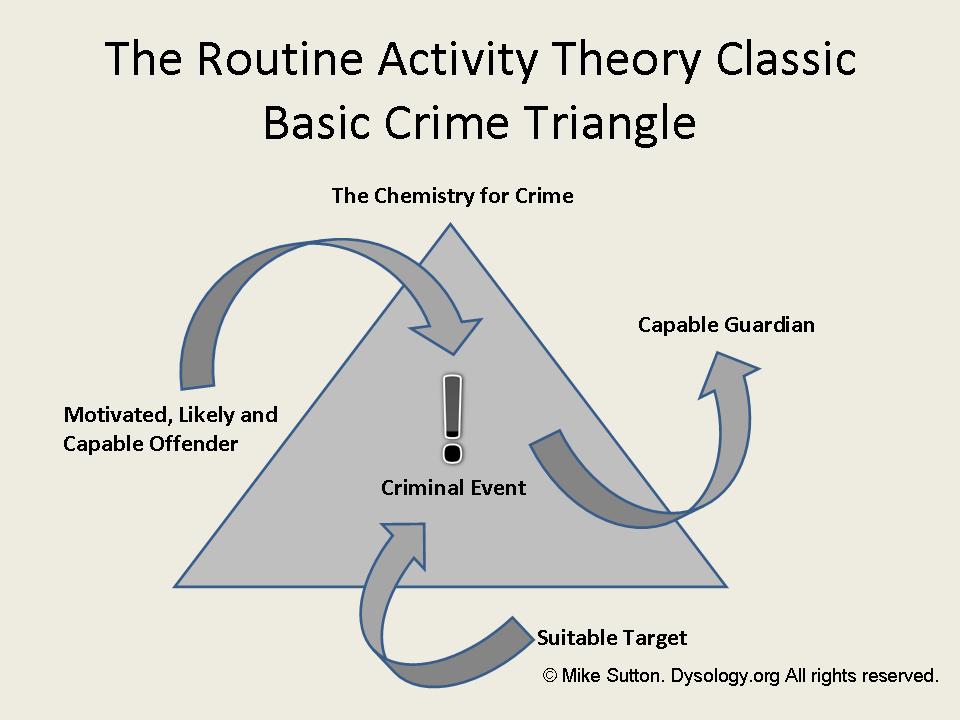

Fig. 1

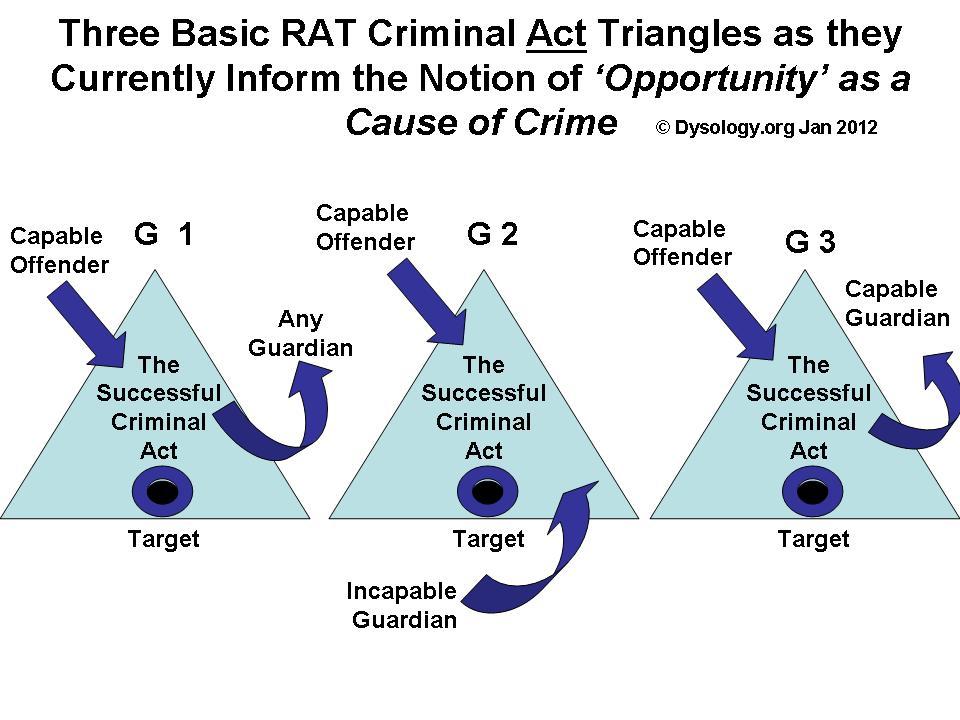

The diagram below (Fig 2) shows the logical variations of how Felson's classic RAT crime triangle (Fig. 1 above) must logically influence RAT's notion of crime opportunity, because Felson does not offer any other theoretical explanation for what makes a crime opportunity. As Fig. 2 reveals, Felson sometimes uses the term ‘absence of guardianship’ to mean (G1) the absence of any person (regardless of their actual intrinsic guardianship capabilities) to serve to create opportunities for crime. By default, the presence of any type of guardian serves to reduce criminal opportunities. And this is a testable hypothesis. For example, to take this hypothesis to the extreme, Crime Scientists might conduct a controlled experiment using life-size cardboard cut outs of people (even mock-police officers) to measure their impact on crime reduction.

On other occasions, as the opposite of Felson's classic G3 explanation for opportunity, RAT's notion of crime 'opportunities' must occur in the presence of incapable guardians (G2). On some occasions, Felson alternately uses guardianship to very specifically mean (G3) ‘capable guardian’, and here he uses its absence to describe the necessary component of a successfully completed crime. By default, therefore, RAT’s G3 ‘capable guardianship’ is either an-as-yet-undiscovered-by-mankind intrinsic and somehow known-in-advance capability that is superior to somehow, as-yet-undiscovered-by-mankind, known-in-advance offender capabilities - or else it must theoretically have been an actually deployed and proven presence that is a necessary component in successfully preventing an attempted crime, not just preventing an otherwise favourable juncture of circumstances for a crime that nobody tried to capitalise upon. Therefore, both G2 and G3 models must underpin the RAT notion of crime opportunity, yet both contain information that cannot be theoretically known until after the theoretical crime has been completed, which makes them both the data of successfully completed crime acts, which makes both G2 and G3 irrefutable truisms, rather than refutable hypothesis that can be empirically tested in the field. This is true, for example, because an offender might attempt to commit a crime in the initial absence of a capable guardian, but then be thwarted when one suddenly turns up. Logically, therefore, only G1 is theoretically capable of existing as an opportunity before the crime is committed.

For the purposes of seeking to achieve clarity, it is perhaps worth examining at this point whether or not there are any implications in the seemingly random interchangeable use by crime opportunity theorists of the terms 'motivated offender' (e.g. Felson 1993; Brantingham and Brantingham 1993), 'likely offender' (e.g. Cohen and Felson 1980; Felson and Boba 2010) and 'potential offender' (Farrell et al 2005). Such seemingly random usage may even occur within texts (e.g. see Farrell et al 2005). To add to the slightly baffling confusion that might arise from the way crime opportunity theorists use these terms interchangeably, they are also known to use them in moderately baffling ways. For example, Brantingham and Brantingham (1993: p. 262) write: 'Neither motivated offenders nor opportunities for crime are uniformly distributed in space and time'. It seems that while such mixing of terminology may be confusing, that, ultimately, these three terms must all mean the same thing. Namely, capable offender. Although the term capable offender does not appear to have been used by any of these authors, the use of all or any of these other three terms in the context of the description of crime provided by RAT basic crime act triangle (e.g. Felson and Boba 2010: p.29) must infer that all of these offender descriptions mean capable offenders (as well as motivated offenders) since they are part of the RAT criminal act triangle only because guardianship is necessarily incapable when such a crime act (other than a failed attempt, which is an outcome that is curiously never considered) occurs.

If crime opportunity theorists were to re-think their definitions, accepting that their RAT notion of opportunity is so different from its etymological meaning that it has no predictive ability, they might seek to develop measurable and findable values for vulnerability, for offender capability, and for offender motivation. These could then be tested by way of prediction, regarding liklihood of successful victimisation in a given time period, and attempted empirical falsification and subsequent improvement. Surely this is what we should expect of a real crime science?

To summarise, you cannot know for sure that a guardian is incapable or capable, relative to an offenders ability, until after a crime has been successfully completed, or else an attempt prevented. It is odd that two out of the three RAT models that must underpin RAT's notion of crime opportunity (G2 and G3) can only be known to exist after the crime is successfully committed. We can see, from this logical analysis, the theoretical limitations that arise as a result of RAT not having a clear definition of opportunity and of its reliance upon both stated and unstated truism models of a completed crime act to create a pseudoscientific notion of opportunity as a cause of crime. In short, the RAT notion of opportunity as a cause of crime is based on the irrational theoretical premise that the crime it seeks to explain caused itself to happen.

Fig. 2

The basic RAT crime triangle (Fig 1) is used in this critique because it is the foundation upon which Felson’s more recent triangle (Fig 3) is built. I contend that the more recent and complex version of the triangle (e.g. see: http://www.popcenter.org/learning/pam/help/theory.cfm) is simply an exercise in overlaying more truisms over the original, which simply overcomplicates and adds multiple layers of tautological complexity to the original.

Fig. 3.

Fallacy of the Social Absolute

The problem with G1 (see Fig 2, above) is that even this model may not even represent reality for most cases of feasibly possible potential crime scenes. To begin to examine this problem we need to ask: what does ‘absence’ of any kind of guardianship mean? Does it mean (Type A) ‘physically absent’ that there are absolutely no other human beings physically around at the potential crime scene? Or does it mean (Type B) ‘conceptually absent’ because they are physically present, but with an absence of any possible or potential-offender-perceived guardianship ability of any kind?

In other words, does (Type B) mean that that there are other human beings physically around (or perhaps CCTV or even faux human beings that aim to fool potential offenders into thinking they are real – such as life size cardboard cut-out police officers), but they do not in reality have the potential or intrinsic ability, or else cannot even create the perception in the mind of the offender that they could prevent the crime? If G1 means (Type A) then it represents an opportunity of that kind, which can be empirically tested. However, if on another occasion G1 means (B) (G1-Type B’) then how can we possibly know for sure, in advance of the crime being successfully completed, that the physically present person is really conceptually absent as any kind of guardian? The answer is that we cannot. A physically present person of any kind may be conceptually absent, to the offender, as any kind of guardian, at the time the offence is being carried out, but that offender may get an unpleasant surprise and find out he/she was wrong.

This means that a ‘G1-Type A’ opportunity is quite easily capable of being known in advance of a successful crime being completed. And that is why this type of RAT opportunity is realistically capable of being empirically tested as a cause of crime (rather than found to be a truism after the event). Fortunately, we probably can test for the impact of a G1-Type B opportunities as a cause of crime as well - so long as we can find ways to know the mind of the offender at the point of the commission of the crime. The use of imaginative mock-crime scenarios may present some potential for future research in this area.

It is by no means a perfect analogy, but one useful example to begin thinking about how G1-Type B opportunities are based on unknowable outcomes are major sporting upsets. Here we must think of the notion of opportunity from the point of view of the contenders. Imagine the title at stake as belonging to the hot favourite and the underdog contender as the ‘thief’ hoping to ‘steal’ the title.

Before the start of a world title boxing match, for example, does the rank-outsider challenger consider the title holder – who’s crown he hopes to ‘steal’ - a capable guardian?

Of the three classic RAT triangles that inform the Opportunity Theory of Crime, only G1 is capable of consideration for this question. And within that model, only G1-Type B can possibly apply.

The excellent boxing website RandyTurpin.Com provides some data on a classic boxing story for us to consider. In the first of two blistering boxing matches the British underdog Turpin caused a major sporting upset by dethroning the American champ Sugar Ray Robinson – a man said by many to be the greatest pound-for-pound boxer who ever lived.

Sugar Ray Robinson v Randolph Turpin I – the data

On July 10th 1951, Robinson was the World Middleweight champion, was 91 fights undefeated, and had lost only once in his 132 fight career. Turpin was British and European Middleweight champion, and had won 40 of his 43 contests. Turpin was widely considered to be way "too young and inexperienced" to defeat the World champion Robinson.

Robinson was 4-to-1 favourite to win. Turpin was 20-to-1 to win on points. Result: Turpin clearly won on points and became the new middleweight boxing champion of the world.

Turpin agreed to a rematch to take place only 64 days later, in New York, USA

Sugar Ray Robinson v Randolph Turpin II - the data.

On September 12th 1951, Turpin was out to prove that his victory was no fluke, whilst Robinson was determined to avenge the defeat and regain the title.

Robinson was a 2-to-1 favourite to win. Turpin a 6-to-4 underdog.

Turpin lost when the fight was stopped in the 9th round due to his failure in that round to fight back against Robinson’s intense punching.

(Q) Taking the logic of the Opportunity Theory of Crime, which is based on the classic RAT 'crime act' triangle, how might we consider the ‘opportunity’ for Turpin to ‘steal’ Robinson’s world title in their first encounter?

(A) Firstly, we could not know in advance that Turpin was a relatively more capable competitor (offender) for the title (target) than Robinson was as owner (guardian) of it. Therefore, G2 and G3 are wrong as explanations of ‘opportunity’ for Turpin to win the title or for Robinson's opportunity to successfully defend it – at least not if we consider an opportunity to be something that exists prior to an action to capitalise upon it. Secondly, G1-Type A does not help us here either, since it requires a physical absence of any kind of guardianship and Robinson was not physically absent from the fight (and neither was Turpin come to that). In terms of the opportunity for Robinson to successfully defend his title - or for Turpin to win it - G1-Type B can only help us if we could know the respective states of either Robinson’s or Turpin's minds in the first boxing match. In the case of Robinson for instance, he might have considered this fight with Turpin to be a G1-Type B opportunity to successfully defend his title, because, prior to knowing the outcome of the fight, there is no other RAT opportunity type. But how did Turpin actually view it? The only possible RAT answer is that Turpin must have seen it as a G1-Type B opportunity as well. This is the only RAT notion of opportunity that is left available for us to consider, and it is far from perfect because to accept it as theoretically sufficient we would have to work on the premise that both fighters absolutely considered the other to be incapable (conceptually absent). Having done a little boxing myself, I very much doubt that would have been the case where two rational professional boxers are concerned.

Furthermore, both the Turpin v Robinson fights serve well our understanding of why RAT G2 and G3 ‘opportunity’ models are merely truisms, as opposed to known and testable entities prior to the commission of the act. Because Robinson was only an incapable guardian of his world title after he lost, as was Turpin only known to be incapable after round 9 in the re-match. In both cases their 100 per cent knowable ‘absence’ as guardians never existed before the event was over. What this example shows us is that it is unlikely that offenders and guardians alike will always consider guardianship in binary terms as either conceptually present or absent. The notion of guardianship in terms of opportunity - prior to action made possible by perception of it - is sometimes (depending on the type of guardianship situation) on a spectrum of perceived capability.

Moving back to crime to consider G1-Type B offenders' perceptions of a person’s potential guardianship capability, we can see an obvious potential personal risk for the offender making a wrong assessment. And this is well evidenced by all those heart warming stories of unlikely ‘have-a-go-heroes’ thwarting an offender's immediate criminal ambition and in the routine hoodwinking of offenders by well disguised police officers acting as prostitutes, drug addicts or other official sting operations. In reality then, it is not only potential offenders, but also potential guardians who may choose to capitalise on a conjunction of favourable circumstances to go after their target.

Of course, the usual day-to-day reality of how offenders asses guardianship is likely to be somewhere in the middle between outright perception of 100 per cent capability or else 100 per cent absence of capability. Meanwhile, at the opposite side of the story to how two skilful and powerful professional boxers are likely to rationally assess one another are those involving drunk offenders. Consider all those – the exception proves the rule - type of news stories. For example, there is the memorable one about a pair of British drunks attacking cage fighters dressed-up as drag-queens, and there are much more serous cases involving drunken thieves, being electrocuted stealing live copper cable. That these stories are exceptional proves the point that it’s really not a binary world involving most offenders making RAT-type decisions about human guardians being 100 per cent capable or not. The latter example should also awaken our academic sensibilities to the importance of our theoretical work in terms of how it influences real-world crime reduction policymaking. Despite my jokes, this subject area is deadly serious because people die from poor policymaking in the field of crime.

Currently, the influence of the self-referential RAT notion of opportunity on knowledge progression is that policy makers and practitioners are being seduced by its unapt simplicity to the extent that they are failing to focus adequately upon where progress could be made by way of understanding more about the role of target vulnerability in opportunity structures for crime. For example, as it is currently understood, the RAT notion of opportunity can only consider an open window to be an opportunity for theft or burglary if the crime is successfully completed. And yet we know, from interviewing them, that burglars do flee homes empty handed if they are disturbed - or if they can find nothing inside worth stealing. Understanding more about the interaction between opportunities and failed attempts is as important for recognising what works in crime reduction as understanding the reasons for successful crimes.

A fourth fallacy then, the fallacy of the social absolute, underpins the RAT notion of crime opportunity, based as it is on the RAT crime triangle where all capable guardianship is absolutely absent. The error of all such binary notions in the affairs of mankind is perfectly explained by William James (2008: p.42):

‘As absolute, or sub specie eternitatis, or quatenus infinitus est. As such, the absolute neither acts nor suffers, nor loves nor hates; it has no needs, desires, or aspirations, no failures or successes, friends or enemies, victories or defeats.'

Seeing reality outside of RAT's impossible notion of opportunity allows us to identify a new and important question for crime opportunity theory that it has, to date ignored. Namely, how does the RAT notion of crime opportunities fit with immediate crime prevention opportunities as they are perceived by different types of guardian? To date, RAT has only considered this element from the perspective of the potential offender. Crime opportunity theorists wishing to analyse G1-Type B offenders' perceptions of guardianship would be making a big mistake if they sought only to measure whether all offenders thought capable guardianship was simply present or absent. Reason suggests that they should seek also to understand to what degree offenders perceive certain types of guardianship relatively inferior to their own abilities and why. Research of this kind, conducted in the field, would enable opportunity theorists to tell the difference between more fully rational choices (those who had a really good rational - weighing up of all the pros and cons - think about it), pseudo-rational choice (those who thought about it just for a bit) and irrational choice (those who were intoxicated, deluded or pretty much totally spontaneous).

For the Offender, if Not RAT and the Law, Theft is a Process